Drought

Drought is generally considered as a deficiency in rainfall /precipitation over an extended period, usually a season or more, resulting in a water shortage causing adverse impacts on vegetation, animals, and/or people.

There is no single, legally accepted definition of drought in India. Some states resort to their own definitions of drought. State Government is the final authority when it comes to declaring a region as drought affected. Union of India has published two important documents in respect of managing a drought.

- Manual for Drought Management[1] (for short "the Manual") prepared in November 2009 by the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture in the Government of India; and

- Guidelines for Management of Drought (for short "the Guidelines") prepared in September 2010 by the National Disaster Management Authority of the Government of India.

However, these documents have no binding force and are mere guidelines to be followed, if so advised.

The Manual recommends four standard monitoring tools- rainfall deficiency, the extent of area sown, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and moisture adequacy index (MAI) - which could be applied in combination for drought declaration. At least three indicators or index values should be adverse for a drought declaration (see the section below for more details). Since the information on these indicators and indices are available at the level of Taluka /Tehsil / Block, drought is declared by the State Government at the level of these administrative units on the basis of observed deficiencies. However, states are not bound to use the above standards for declaration of drought and many states still depend on the failure of crop measures to declare a drought (but indicators based on crop failure prevents the farmers from getting any early help)

The Supreme Court of India in its verdict dated 11 May 2016 in the matter of Swaraj Abhiyan Vs Union of India (W.P. (C) No. 857 of 2015) stated that drought would certainly fall within the definition of “disaster” as defined under Section 2(d) of the Disaster Management (DM) Act, 2005. The DM Act defines "disaster" to mean ‘a catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence in any area, arising from natural or man-made causes, or by accident or negligence which results in substantial loss of life or human suffering or damage to, and destruction of, property, or damage to, or degradation of, environment, and is of such a nature or magnitude as to be beyond the coping capacity of the community of the affected area.'

Since drought is a disaster, risk assessment and risk management as well as crisis management of a drought falls completely within the purview of the Disaster Management Act, 2005. Accordingly Supreme Court directed the National Disaster Management Authority to be the agency responsible for drought management particularly with respect to chalking out long term preventive and mitigation measures. However, the state government concerned would be the final authority to declare a drought.

The Supreme Court in its 11 May 2016 verdict has made it clear that it is not as if a drought is required to be declared in the entire State or even in an entire district. If a drought-like situation or a drought exists in some village in a district or a taluka or tehsil or block, it should be so declared.

Further the Supreme Court stated that the failure of the States to declare a drought (if indeed that is necessary) effectively deprives the weak in the State, the assistance that they need to live a life of dignity, as guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution [2].

Features of drought

The 2010 Guidelines for Management of Drought issued by National Disaster Management Authority characterises drought as a natural hazard that differs from other hazards since it has a slow onset, evolves over months or even years, affects a large spatial extent, and cause little structural damage. Its onset and end and severity are often difficult to determine. Like other hazards, the impacts of drought span economic, environmental and social sectors and can be reduced through mitigation and preparedness.

The concept of drought varies from place to place depending upon normal climatic conditions, available water resources, agricultural practices and the various socio-economic attributes of a region. Arid and semi arid areas are most vulnerable where drought is a recurring feature occurring with varying magnitudes.

However, this traditional approach to drought as a phenomenon of arid and semi-arid areas is changing in India too. Now, even regions with high rainfall, often face severe water scarcities. The Guidelines point out the ‘changing face’ of drought in India with examples of Cherrapunji in Meghalaya and Jaisalmer in Rajasthan. Cherrapunji in Meghalaya, one of the world’s highest rainfall areas, with over 11, 000 mm of rainfall, now faces drought for almost nine months of the year. On the other hand, the western part of Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan, one of the driest parts of the country, is recording around 9 cm of rainfall in a year.

Impact of droughts

In the past, the impact of drought has been linked mostly to the agricultural sector, as deficiency of precipitation over an extended period of time, results in depletion of soil moisture, which in turn reduces crop production. This impact continues and is increasing as poor land use practices, rapidly increasing populations, environmental degradation, poverty and conflicts reduce the potential of agricultural production. The extent and intensity of drought impact is determined by prevailing economic conditions, the structure of the agricultural sector, management of water resources, cereal reserves, internal and external conflicts etc. The micro level impact is at the village and household levels. Generally, the secondary impact is on regional inequality, employment, trade deficits, debt and inflation. Drought can result in household food insecurity, water related health risks and loss of livelihood in the agricultural as well as other sectors of the economy.

Classification of drought in India

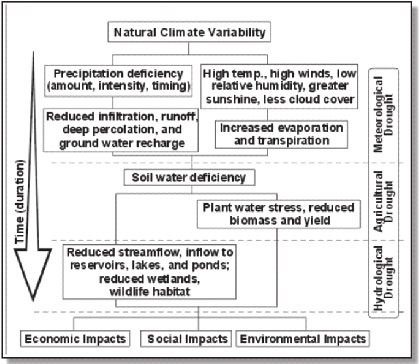

The 2009 Manual of Drought Management issued by Ministry of Agriculture, Union of India (prepared for Ministry by National Institute of Disaster Management) classifies droughts into three categories based on the existing literature on the subject:-meteorological, agricultural and hydrological. The manual also specifies the India specific features for each type of these droughts.

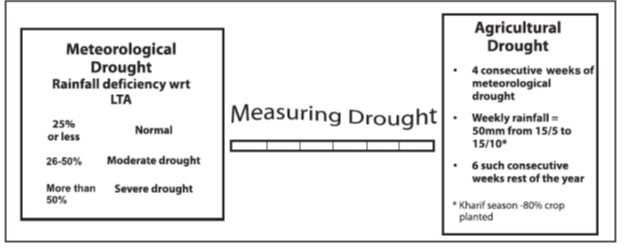

- Meteorological drought is defined as the deficiency of precipitation from expected or normal levels over an extended period of time (i.e. normal levels accommodate upto 10% deviation from long term average). Meteorological drought usually precedes other kinds of drought and is said to occur when the seasonal rainfall received over an area is less than 25% of its long-term average value. It is classified as moderate drought if the rainfall deficit is 26-50% and severe drought when the deficit exceeds 50% of the normal.

- Hydrological drought is best defined as deficiencies in surface and sub-surface water supplies leading to a lack of water for normal and specific needs. Such conditions arise, even in times of average (or above average) precipitation when increased usage of water diminishes the existing reserves.

- Agricultural drought is usually triggered by meteorological and hydrological droughts and occurs when soil moisture and rainfall are inadequate during the crop growing season causing extreme crop stress and wilting. The relationship of agricultural drought to meteorological and hydrological drought is shown in the graph. Plant water demand depends on prevailing weather conditions, biological characteristics of the specific plant, its stage of growth and the physical and biological properties of the soil. Agricultural drought arises from variable susceptibility of crops during different stages of crop development, from emergence to maturity. In India, it is defined as a period of four consecutive weeks (of severe meteorological drought) with a rainfall deficiency of more than 50 % of the long-term average or with a weekly rainfall of 5 cm or less from mid-May to mid-October (the kharif season) when 80% of India’s total crop is planted or six such consecutive weeks during the rest of the year.

Source: National Weather Service, United States, Public Facts on Drought

Measuring Meteorological and Agricultural Drought in India

Source: Manual on Drought Management (2009)

The classification of drought as mentioned above need not be the only criteria for classification.[3]"

Droughts are also classified according to the timing of rainfall deficiency during a particular rainfall season, usually June to September in India. Thus, on the basis of time of onset, drought is also classified as early season, mid season and late season.

This classification is particularly useful while monitoring the drought. The monitoring or the possibility of a drought does not end in July or early August but continues till the end of September and in some situations till the end of November (where North West Monsoon showers are received).

The Guidelines provide that to promote management of relief measures in near real time it is necessary to declare early season drought by end of July, mid season drought (growing season) by end of September and end season by November.

Early season droughts provide sufficient lead-time to mitigate the impact of drought. Mid-season droughts occur in association with the breaks in the southwest monsoon. If the drought conditions occur during the vegetative phase of crop growth, it might result in stunted growth, low leaf area development and even reduced plant population.

Definition of "drought year" adopted by IMD for the whole of India

A drought year as a whole is defined by the To IMD/Welcome.php Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) as a year in which, the overall rainfall deficiency is more than 10% of the Long Period Average value (LPA) value and if more than 20% of its area is affected by drought conditions, either moderate or severe or combined moderate and severe.

When the spatial coverage of drought is more than 40% it will be called as All India Severe Drought Year[4].

Declaration of Agricultural Drought in India (Early Indicators developed for identifying the Agricultural drought)

Traditionally in India, District Collectors recommend the declaration of drought only after crop production estimates are obtained through the annewari / paisewari / girdawari system (essentially means value of crops; it is often measured as the value of the actual yield after harvest in relation to the value of the crop grown; this system provides an estimate of agricultural losses, which could be used as an indicator of drought). Generally, areas with less than 50% annewari / paisewari / girdawari are considered to be affected by a drought. Final annewari / paisewari / girdawari figures for kharif crops are available only in December, while those for rabi crops are available in March.

After drought declaration, planning and implementation of drought relief and response measures is initiated.

Collectors can notify drought only after the State Government declares drought in the State or parts thereof. Financial Assistance is provided through the Calamity Relief Fund (CRF) / state disaster response fund[5] maintained by the state under the administrative jurisdiction of state disaster management departments.

After drought is declared, if the funds available under the Calamity Relief Fund (CRF) / State Disaster Response Fund are inadequate for meeting relief expenditures, the State Governments may consider submitting a Memorandum for assistance from the National Calamity Contingency Fund (NCCF) / National Disaster Response Fund[6] . The Government of India sends a team to assess the requirement for relief and based on that Govt of India release assistance from the NCCF/NDRF (This means that if drought is declared in January or February, the team would visit much after the crop is harvested and thus cannot assess crop losses.). The revised norms for assistance from SDRF / NDRF were issued on 8 April 2015 covering the period 2015-2020.

The 2010 guidelines on drought management had recommended replacing the annewari / paisewari / girdawari system by using new indicators which facilitate early determination of drought. It recommended declaring early season drought by end of July, mid season drought (growing season) by end of September and end season drought by November.

The 2009 manual points to different indices that could be used in early determination of drought

- Aridity Anomaly Index (AAI) / Rainfall deviation Index

- Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI)

- Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI)

- Crop Moisture Index (CMI)

- Surface Water Supply Index (SWSI)

- Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

- Moisture Availability Index (MAI)

- Effective Drought Index (EDI)

From the above, it has identified four key indices which could be used in combination to declare a drought by the state concerned.

- Key Index 1: Rainfall Deficiency: The Manual categorically states that rainfall is the most important indicator of drought. A departure in rainfall from its long-term averages should be taken as the basis for drought declaration. The IMD [Indian Meteorological Department] can provide rainfall data to the State Government, which can also collect data through its own network of weather stations. According to the IMD, drought sets in when the deficiency of rainfall at a meteorological sub-division level is 25 per cent or more of the Long-Term Average of that sub-division for a given period. The drought is considered “moderate”, if the deficiency is between 26 and 50 per cent, and “severe” if it is more than 50 per cent.

The manual states that the State Government could consider declaring a drought if the total rainfall received during the months of June and July is less than 50% of the average rainfall for these two months

or

if the total rainfall for the entire duration of the rainy season of the state, from June to September (the south-west monsoon) and or from December to March (north-east monsoon), is less than 75% of the average rainfall for the season

and

there is an adverse impact on vegetation and soil moisture, as measured by the vegetation index and soil moisture index.

IMD identifies drought in all the meteorological sub-divisions (aridity anomaly index).

- Key Index 2: Area under Sowing: Drought conditions could be said to exist if the total sowing area of kharif (Rabi crops) is less than 50% of the total cultivable area by the end of July / August (November/December in case of rabi crops), depending upon the schedule of sowing in individual states. In such situations, even if rainfall revives in the subsequent months, reduction in the area under sowing cannot be compensated for and the agricultural production would be substantially reduced.

- Key index 3: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): NDVI is an index indicating the density of vegetation on earth based on the reflection of visible and near infrared lights detected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer instrument from a remote sensing satellite. The values obtained for a given NDVI always ranges from –1 to +1. A negative number or a number close to zero means no vegetation and a number close to +1 (0.8-–0.7) represents luxurious vegetation. States could declare drought only when the deviation of NDVI value from the normal is 0.4 or less. However, the NDVI cannot be invoked for the declaration of drought in isolation from the other two key indicators.

For declaring drought, States need to obtain NDVI values through the National Agricultural Drought Assessment and Monitoring System (NADAMS) managed by Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Centre. The 14 States covered under NADAMS are Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. The drought assessment for 14 States is carried out at District level. However, out of these 14 States in 5 States (Andhra Pradesh, Haryana, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana) drought assessment is carried out at Sub-District level. All the above-mentioned States receive NADAMS reports on a regular basis. Those States which do not receive the report can approach the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC) for receiving the information. The agriculture drought assessment and monitoring, under NADAMS project, is carried out using multiple satellite data, rainfall, soil moisture index, potential sowing area, irrigation percentage and ground observations. A logical modeling approach is followed to classify the districts into Alert, Watch and Normal during June, July and August and Severe, Moderate and Mild drought conditions during September and October. The monthly Drought Assessment Reports are communicated to all concerned State and national level agencies and also kept on the Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Centre (MNCFC) website. NADAMS project provides an early assessment of drought situation and thus helps the State Governments to take remedial measures and also use this information for drought declaration.

- Key index 4: Moisture Adequacy Index (MAI): MAI is based on a calculation of weekly water balance and is a ratio expressed as a percentage of actual to potential evapo-transpiration[7]. If the water balance percentage is between 76 and 100 there is no drought; between 51 and 75 there is mild drought; between 26 and 50 there is a moderate drought and below 25 there is a severe drought. Water balance calculation takes into account the soil characteristic, crop growth period and water requirements of major crops. (The type of soil is also a relevant consideration; for instance, despite many parts of the State being inundated with water, MAI will be low due to the type of soil.) Drought is specified crop-wise on a real-time basis.

MAI values are critical to ascertain agricultural drought. The State agriculture department needs to calculate the MAI values on the basis of data available to it and provide it to the Department of Relief and Disaster Management, which would ascertain that MAI values conform to the intensity of moderate drought before drought is declared. MAI values need to be applied in conjunction with other indicators such as rainfall figures, area under sowing and NDVI values.

At Least three of the above four factors must be present for the declaration of drought.

Owing to the sparse network of ground-based observations available in the country, monitoring of drought suffers from the following deficiencies:

- Forecasts are general in terms of space and time while the specific needs are at the local level;

- The timing does not match user needs;

- Information received from different sources sometimes has conflicting messages; and

- The language is not clearly understood by users.

The manual on drought management states that ideally, States should declare drought in October. The monsoon is over by this month and figures for total rainfall are available in this month. Similarly, a final picture regarding the crop conditions as well as the reservoir storage is available by the end of October. It provides adequate time for the central team to visit the State and assess the crop losses. For the States that receive rains from the north-east monsoon, drought declaration should be done in January. However, if the situation so warrants, such a declaration could be made earlier as well.

Center- state Jurisdiction with respect to declaration of drought

The Manual /Guidelines for Drought Management and the indicators mentioned above are used only as a reference document as well as guide for action by policy makers, administrators and technical professionals. While Government of India recommends these guidelines, it also recognizes that the State Government could face situations under which they may need to deviate from these guidelines and acknowledges the freedom to do so. The manual does not in any way reduces the state government authority to take their own decisions in a drought situation. This is necessary as there might be situations which do not find mention in the manual and some states are more irrigated than others and hence, are not so dependent on rainfall vis-à-vis other states. The requirement of water is also dependent on the type of crop sown and even when there is deficit rainfall, the crop production does not necessarily fall to that extent in all states. Accordingly, in a federal polity, GOI is of the view that it may not be justified to issue binding guidelines for all states to declare drought and to sit in judgment on their decisions.

For instance, Haryana, where 83% of the area is under irrigation, banks upon other factors for not declaring a drought, such as: (i) Extent of fodder supply and its prevailing prices compared to normal prices; (ii) Position regarding drinking water supply; (iii) Demand for employment on public works, and unusual movement of labour in search of employment; (iv) Current agricultural and non-agricultural wages compared with normal times; (v) Supply of food grains, and (vi) price situation of essential commodities, which could be applied by the State, in combination, for drought declaration. Similarly, Bihar has added some other factors such as perennial rivers while Gujarat has added factors such as the nature of the soil etc. The Gujarat Relief Manual, apparently refers to “scarcity” and “semi-scarcity” instead of the words “drought” or a drought-like situation. Similarly, due to a lack of standardization in the annewari system of crop assessment, Gujarat takes 4 annas out of 12 annas as a base for determining if there is a drought-like situation. In areas where the crop cutting is between 4 annas and 6 annas, there is discretion in the State Government to declare or not to declare a drought. On the other hand, Maharashtra uses 50 paise as the standard for the annewari system for declaring a drought.

The Supreme Court in its 11 May 2016 verdict affirmed that the final decision to declare a drought is of the State Government but the resources available with the Union of India can be effectively used to assist the State Governments in having a fresh look into the data and information and to arrive at the correct decision in the interest of the affected people of the State. The Supreme Court commented that Union of India cannot totally wash its hands off on issues pertaining to Article 21 of the Constitution but at the same time, the authority of the State Government to declare a drought or any other similar power cannot be diluted.

In Union of India, under the Allocation of Business Rules of the Government of India and as per the for National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF).pdf Guidelines on the constitution of NDRF/SDRF, the matters relating to damage to crops and co-ordination of relief measures necessitated by drought, hailstorm and pest-attacks, cold wave and frost and the matters relating to loss of human life due to drought fall within the domain of the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare. The Ministry of Land Resources and the Ministry of Water Resources too are mandated to undertake drought proofing activities.

Supreme Court (SC) Directions on 11 May 2016 with respect to drought management

The major directions issued by the Supreme Court on 11 May 2016 are as follows:

- As mandated by Section 44 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 a National Disaster Response Force with its own regular specialist cadre is required to be constituted. However, no such force has been constituted till date. Accordingly, SC directed the Union of India to constitute a National Disaster Response Force within a period of six months from date of judgment with appropriate and regular cadre strength.

- As mandated by Section 47 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 a National Disaster Mitigation Fund (for taking measures aimed at reducing, inter alia, the risk of a disaster or threatening disaster situations) is required to be established. But, no such Fund has been constituted till date. Accordingly, SC directed the Union of India to establish a National Disaster Mitigation Fund within a period of three months from the date of judgment.

- Section 11 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 requires the formulation of a National Plan relating to risk assessment, risk management and crisis management in respect of a disaster. Such a National Plan has not been formulated over the last ten years, although a policy document has been prepared. Accordingly SC directed the Union of India to formulate a National Plan in terms of Section 11 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 at the very earliest and with immediate concern. Corresponding obligations have been placed on the State Governments under the provisions of the DM Act not only with regard to the State but also with regard to each District in the State. (On 1 June 2016, Government released the National Plan.)

- The Drought Management Manual was published in 2009 and several new developments have since taken place requiring it to be revised. SC directed that the Manual be revised and updated on or before 31st December, 2016.

- While revising and updating the Manual, the Ministry of Agriculture in the Union of India was directed to take into consideration inter-alia, the following factors:

- Weightage to be given to each of the four key indicators should be determined to the extent possible. (Although the Manual states that rainfall deficit is the most important indicator, State Governments seem to be giving greater weightage to the area of crop sown out of the cultivable area and not to rainfall deficit. For this reason, necessary weightage is required to be given to each key indicator.)

- The time limit for declaring a drought should be mandated in the Manual.

- The revised and updated Manual should liberally delineate the possible factors to be taken into consideration for declaration of a drought and their respective weightage.

- While it may be difficult to lay down specific parameters and mathematical formulae, the elbow room available to each State enabling it to decline declaring a drought (even though it exists) should be minimized, in the interest of the people who face distress because of a drought or a drought-like situation.

- The nomenclature should be standardized as also the methodology to be taken into consideration for declaring a drought or not declaring a drought.

- In the proposed revised and updated Manual as well as in the National Plan, the Union of India must provide for the future in terms of prevention, preparedness and mitigation. Innovative methods of water conservation, saving and utilization (including ground water) should be seriously considered and the experts in the field should be associated in the exercise.

- The Government of India must insist on the use of modern technology to make an early determination of a drought or a drought-like situation. Government of India should insist on the use of such technology in preparing uniform State Management Plans for a disaster.

- Humanitarian factors such as migrations from affected areas, suicides, extreme distress, the plight of women and children are some of the factors that ought to be kept in mind by State Governments in matters pertaining to drought and the Government of India in updating and revising the Manual. Availability of adequate food grains and water is certainly of utmost importance but they are not the only factors required to be taken note of.

References

- Press release of Ministry of Agriculture dated 03-May, 2016

- Supreme Court Verdict in the matter of Swaraj Abhiyan Vs Union of India W.P. (C) No. 857 of 2015 dated 11 May 2016

- NCFC Newsletter April 2016

- FAQ of IMD

- Disaster Management Act, 2005

- Manual for Drought Management prepared in November 2009 by the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture in the Government of India

- Guidelines for Management of Drought prepared in September 2010 by the National Disaster Management Authority of the Government of India

- Government Notification regarding Constitution of NDRF and SDRF on for National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF).pdf 28 September 2010 and its reconstitution on July 2015 based on 14th Finance Commission Recommendations

- Norms for Assistance from SDRF and NDRF for the period 2015-2020 dated 8 April 2015

- Chapter 10 of 14th Finance Commission Recommendations in respect of handling disaster management funds

- Report of the Estimates Committee 2009-2010 on Drought Management, Foodgrain Production And Price Situation & the Action Taken Report of the Estimates Committee 2010-2011 on Drought Management, Foodgrain Production And Price Situation

- Drought Prone Areas Programme

- Outcome Budget of Ministry of water Resources of the year 2016-17